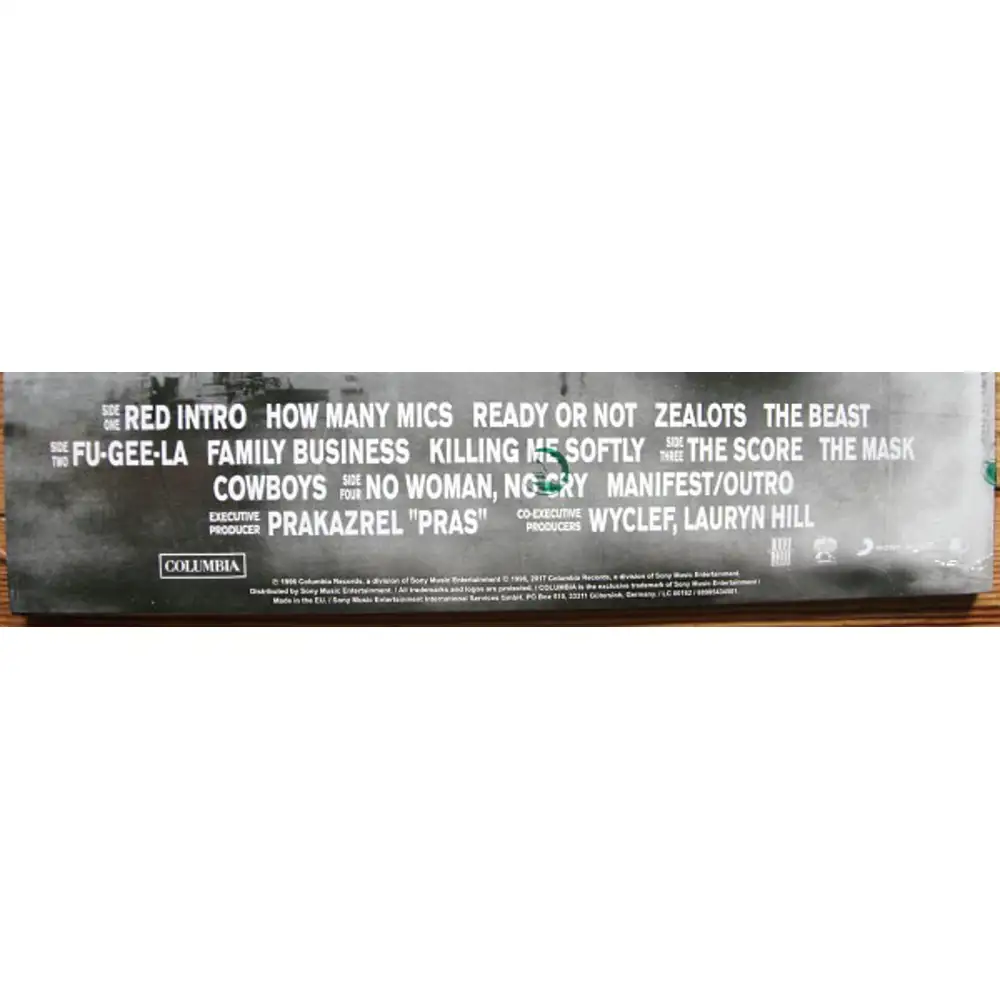

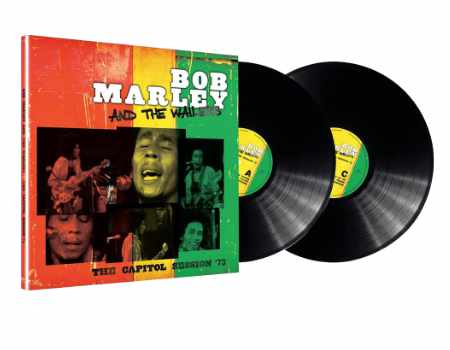

My dream entertainment room | Source: Pinterest Has the significance of album art diminished since the employment of digital music online? Do artists and record companies even focus on creating visual masterpieces to complement their aural work? How do the visuals of music - be it music video or album art - affect the manner in which it is mediated? This interplay between audio and visual can either strengthen or dismantle our notion for signs can be delivered. Cover art for records like The Beatles’ Abbey Road, Stevie Wonders’ Songs in The Key of Life and even Fugees’ The Score has made it on to lists for “Best Cover Art of All Time.” How do these artifacts compare to posters sold in retail shops? My parents and other relatives often mocked me for getting posters out of magazines, insisting that “nothing can compare” to using vinyl art as bedroom décor. Vinyls also contributed itself as a galleria artifact - a thing to be admired or envied upon display. How did the idea of race as a social construct infiltrate the impact of music and of producing album art? Some record companies did not allow for many artists to have their faces on album covers according to their race and the musical genre. Prior to music videos or recorded live performances, there was an ambiguity attached to music where the artist’s identity was either implicitly or explicitly hidden. Therefore, it is not just sounds, but visuals that are being mediated. Some digital music playback systems – specifically Pandora – display album art as songs play. And while the cost of concerts and vinyl records may be a deterring factor in its competition with mp3 sales, the quality is at the heart of the matter for most of these traditional aficionados, not the quantity. Similarly, it is a richer experience to indulge in a live acoustic performance versus running over to YouTube to catch video of the same event. It is this appreciation for tangibility that has sparked a resurgence in vinyl record sales. There’s something sweet about listening to an entire album untouched, no clicking or tapping of a screen, as you would with a vinyl record. I may be negating myself a bit here, but in making the access to music more efficient – placing it on our mobile cellular devices – we intensify the immediate gratification, quick-triggered satisfaction/obtainment of an art form.

I believe the current minimal effort behind listening to a musical composition devalues its essence.

As McLuhan’s tetrad of technology lays out, just as we advance, we risk obsolescence. While digital music files and playback lessen the need for tangible artifacts, the transformation of the medium has altered the art form. And while both appeared to be on the opposite ends of the spectrum argument, their interaction proved them both to be a part of a broader ecosystem – a media system. As Professors Ribes and Irvine discussed, Apple and Adobe became one another’s archrivals based on the functionality of their respective products. Dialectically speaking, one cannot die when it is constantly being acknowledged in comparative discourses. The mere discussion of vinyls in the age of mp3 files and Bluetooth-capabilities for music playback is reflective of how a technology – more so, a medium – cannot be eradicated. One medium that I am steadily becoming fascinated with is the vinyl record partly, because I’m a minimalist and partly, because my mom’s 45s are sitting in my living room, begging for some airtime. The manner in which this content is transmitted to and from analog and digital formats is through mediation. For the past weeks, we have examined the poignancy of a particular text, whether it was Daft Punk, Andy Warhol or “Ayo.” This week, we devote our conversation to the artifacts that allow our senses to consume this content, information or media, if you will – the medium.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)